Elmers Jolanda1 and Panes Mathilde1

1 Medical Library, Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Corresponding author: Panes Mathilde, mathilde.panes@chuv.ch

Abstract

Introduction: At the medical library of the University of Lausanne, book circulation is decreasing, while student affluence in the reading rooms and space use are steady. We decided to analyze the reading habits among medicine students at the University of Lausanne, in order to understand their needs and preferences, and to obtain an insight for further library development.

Problem: Are students still using books to study or are they using other information carriers? How can the library fulfil students’ needs when it comes to their reading preferences?

Methodology: Initially we conducted a literature review to gather data about reading habits among medicine students. We looked for recent articles (from the last 8 years) because significant changes in electronic devices for information resources. In order to gather quantitative data we then surveyed medical students from grade 1 to 6 of the bachelor and master programs, through an online questionnaire to know more about their reading habits. We researched the time allocated for reading, the type of resources used (course handouts, articles, monographs, web pages, multimedia, etc.), the preference for electronic or print, and their information acquisition (personal purchase, course material, material borrowed at the library, open access, pirated copy).

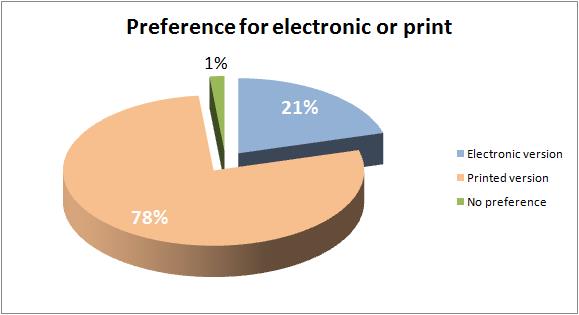

Results: The results of our survey show that handouts are the most used resource: 99 percent of our sample uses them as their primary source to study with. For all text resources, students indicate that they prefer the printed version over a digital version.

Key words:

- Reading,

- Learning,

- Habits,

- Students, medical,

- Education, Medical, Undergraduate,

- Education, Medical, Graduate

- Switzerland

Introduction

Book circulation is decreasing at the medical library of the University of Lausanne, while student affluence in the reading rooms and space use are steady. We decided to analyze the reading habits among medicine students at this university in order to understand their needs and preferences and obtain an insight for further library development.

Problem

Book circulation among medical students is decreasing at the medical library of the University of Lausanne. Are students still using books to study or are they using other information carriers? How can the library fulfill students’ needs when it comes to their reading preferences?

Methodology

Initially we conducted a literature review to gather data about reading habits among medicine students. We looked for recent articles (published in the last eight years) to observe the effects of the significant changes in electronic devices for information resources. A research in the databases PubMed, Francis and Eric, as well as the editorial platform ScienceDirect, returned several articles about reading and learning habits of students in different institutions around the world.

However, those studies were not enough to have a clear picture of how to better serve the medical students in Lausanne. In order to gather quantitative data on reading habits, we then surveyed medical students from year one to six of the bachelor and master programs through an online questionnaire. The questionnaire contained 13 questions and was sent to 1640 students, who could access it for a period of 18 days.

We researched the time allocated to reading for their studies, the type of resources used (course handouts, articles, monographs, web pages, multimedia, etc.), the preference for electronic or print, and their information acquisition methods (personal purchase, course material, material borrowed at the library, open access, pirated copy).

Finally, we also extracted data about the number of loans and renewals per year from our integrated library system.

Results:

We will discuss our findings in this part, starting with a literature review of reading practices among students. We will also discuss book loan and renewal’s statistics and comment on the data we gathered through our survey.

Literature research overview

Our research focuses on whether our students prefer paper-based or electronic versions of their academic reading material.

In order to give a context for our research into the reading habits of the students of the medical faculty of the University of Lausanne, we conducted a literature research into students’ experience with paper-based reading, compared to onscreen reading. At the start of our thinking process, we suspected that the quality of the electronic reading support (portable device or screen) affects the attitude of the student towards the medium used for reading. However, we also supposed that improvements in electronic reading devices and screen technology had an impact on the preference of the students. Our interest for this literature study was, therefore, in recent research outcomes where improvements in technological interfaces are taken into consideration.

On her research about 196 students’ habits, Stoop finds that they still prefer paper-based reading when texts are longer and more elaborate. However, students show a preference for electronic versions for quick information gathering, communication and navigation (1). Moreover, by questioning 91 students on their preferences, Woody concludes that students do not prefer e-books over textbooks, regardless of their gender, computer use or comfort with computers, even if they had used e-books before (2).

Both Vandenhoeck and Stoop remark that onscreen reading does not allow for annotation of text, such as underlining, highlighting, sticky notes and dog ears. Even though electronic devices offer different ways of highlighting and note taking, these are not perceived the same as interacting directly with the text on paper by the student (3, 4). Mangen confirms this finding, and adds that when reading long linear texts “the reader needs spatiotemporal markers to aid memory and reading comprehension”. According to his research, scrolling through a long text on a computer does not have the same effect on reading comprehension as turning pages (5).

While interviewing ten students about their experiences with reading, Rose remarks that texts that were originally created as paper-based documents do not allow for comfortable on-screen reading (6). This is confirmed by Rockinson-Szapkiw, who states that “learning can be impacted by both the format of the text and the medium through which the text is consumed” (7).

In a research with 298 students, Daniel and Woody found that students spent significantly more time reading the same text on electronic media than on paper. However, after evaluating the effects of the reading through a quiz, they found no difference between the performance of students who read on paper and of those who read the text on electronic devices (8).

Even though several researchers confirm that today there are very few differences in performance when students take tests after studying texts in different formats (9), research still shows that students have a strong preference for paper-based reading. Myrberg and Wiberg suspect that habits and attitudes lead mostly to students’ preference for paper-based texts. They conclude that the current technology does not respond to the shortcomings of screens regarding spatial landmarks, which is the reason why readers still return to print-based resources: touching paper and turning pages are needed in the reading and learning process (10).

Situation at the medical library of the university of Lausanne

Loan statistics

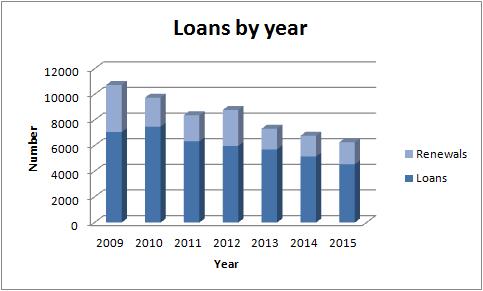

The figures below clearly show a decrease in the number of book loans per year in the last six years.

A decrease in loans can be explained by several factors, like the adequacy of the library collection considering the topics studied in class and the bibliographies recommended by professors during the courses. It could also indicate a change of methodology in the process of information acquisition; a shift from the use of books to the use of handouts to prepare for exams.

When planning for the future of the medical library, the management will have to take strategic decisions regarding the space used. In the past five years, the collection of printed journals has been removed from the library, and more space has been allocated to provide students with more space to study. Users can consult most of the journals online when they are on campus, using the subscriptions available at the University of Lausanne and the university hospital. The eBook collection is smaller and still developing.

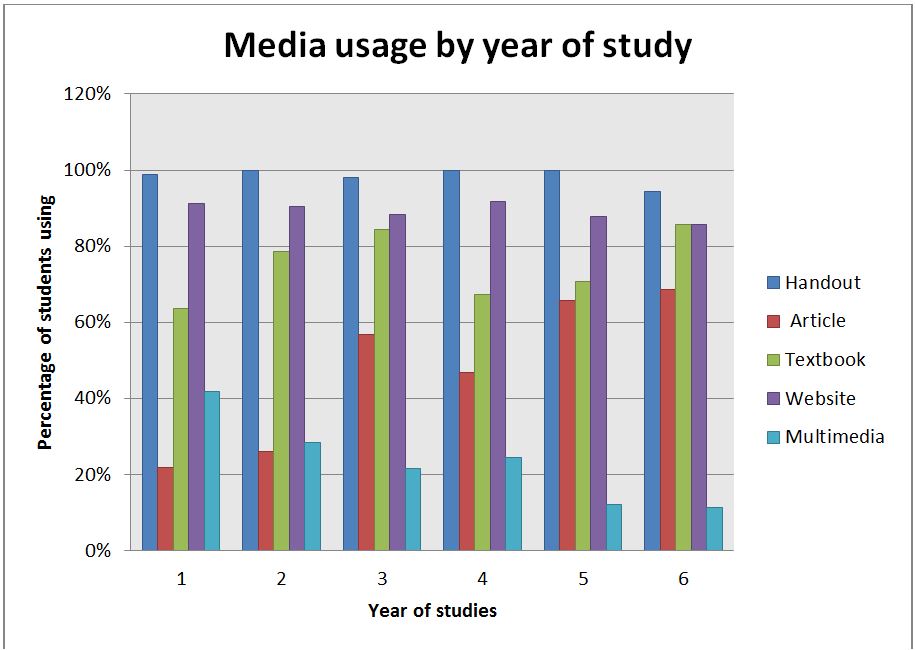

However, the library collection is becoming less important for the students, especially during the first years of their degree. As shown in the graphs below, they mainly base their exam preparations on the handouts provided in their courses.

Survey results on information carriers’ used to study

Based on our survey, we could visualize practices among medicine students, and we can conclude that print-on-paper is the preferred medium for most students of the medical faculty of the University of Lausanne.

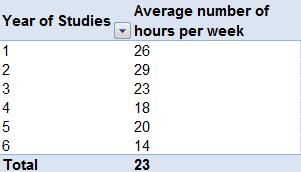

In the very competitive environment of studies in the medical field, we can expect students to spend much time studying. We questioned them on the amount of time spent studying in general in an open question, and asked them how much time was spent on specific information resources, in a time range breakdown. The average total time dedicated to studying shows a mean of 23 hours per week.

Time spent studying per year of studies

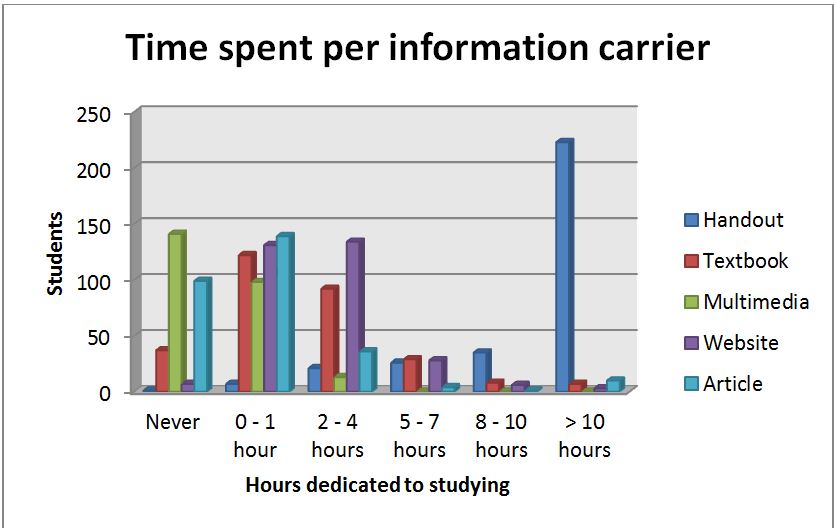

The result of our survey shows that handouts are the most used resource: 98 percent of our sample study with it. Websites follow with 89 percent use, textbooks are used by 72 percent of the students. Scientific articles are used by 43 percent of the students. Multimedia is the least used resource, with 26 percent. A possible explanation for the high use of course handouts is the pressure put on students to pass standardized exams. At the University of Lausanne, standardized exams such as multiple choice tests are the norm in the first grades of medical studies. To increase their chance of success in the exam session, it seems likely that students will use material given by the professor, because other sources of information are less likely to get tested. Usage of other resources might be needed to clarify a specific topic, but not to expand the area of study.

We surveyed the students about how much time they spent studying per different media type. The results show that by far the largest number of students spends most of their study time using the handouts they receive in their courses. Very little time is spent using other media. In our analysis, we discovered a significant increase of the use of scientific articles from the third year on. Multimedia usage is low for all years, but is significantly more used in the first year. Handout usage only decreases on the sixth year.

The following figure shows that for all types of media, students said they preferred a printed version of the document.

In our literature review, we highlighted the difficulty of annotating on screen. In the process of reading for learning, having the possibility to write down extra information on the document is certainly a factor of importance in the preference for printed sources.

Conclusion

With our study, we confirmed that the body of students is not yet interested in shifting medium (from paper to electronic) to study. We also learned important facts: as course handouts are the most important source for students, the library is more a place to study than a source of information, at least during the first years of medical studies. The acquisition policy for this specific audience must remain closely linked to the bibliographies handed out by professors of the faculty. We also argue that teachers should encourage students to investigate and expand their knowledge instead of limiting themselves to memorize what is handed to them in class. As websites are a commonly used source of information, the library should offer more support in online information assessment, in order for the students to be better equipped to evaluate the available resources. This snapshot of habits and preferences should be renewed on a yearly basis in order to progressively adapt to the changing needs of the students.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stoop J, Kreutzer P, Kircz JG. Reading and learning from screens versus print: a study in changing habits: Part 2 – comparing different text structures on paper and on screen. New Libr World. 2013 Sep 30;114(9/10):371–83.

- 2. Woody WD, Daniel DB, Baker CA. E-books or textbooks: Students prefer textbooks. Comput Educ. 2010 Nov;55(3):945–8.

- 3. Stoop J, Kreutzer P, Kircz J. Reading and learning from screens versus print: a study in changing habits: Part 1 – reading long information rich texts. New Libr World. 2013 Jul 12;114(7/8):284–300.

- 4. Vandenhoek T. Screen Reading Habits among University Students. Int J Educ Dev Using Inf Commun Technol. 2013;9(2):37–47.

- 5. Mangen A, Walgermo BR, Brønnick K. Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension. Int J Educ Res. 2013;58:61–8.

- 6. Rose E. The phenomenology of on-screen reading: University students’ lived experience of digitised text. Br J Educ Technol. 2011 May 1;42(3):515–26.

- 7. Rockinson- Szapkiw AJ, Courduff J, Carter K, Bennett D. Electronic versus traditional print textbooks: A comparison study on the influence of university students’ learning. Comput Educ. 2013 Apr;63:259–66.

- 8. Daniel DB, Woody WD. E-textbooks at what cost? Performance and use of electronic v. print texts. Comput Educ. 2013 Mar;62:18–23.

- 9. Eden S, Eshet-Alkalai Y. The effect of format on performance: Editing text in print versus digital formats: The effect of format on performance. Br J Educ Technol. 2013 Sep;44(5):846–56.

- 10. Myrberg C, Wiberg N. Screen vs. paper: what is the difference for reading and learning? Insights [Internet]. 2015 Jul 7 [cited 2016 Apr 17];28(2). Available from: http://insights.uksg.org/articles/10.1629/uksg.236/