Sharon Stevens, Shiona Aldridge and Alison Turner

Midlands and Lancashire Commissioning Support Unit, West Bromwich, UK

Contact: sharon.stevens7@nhs.net

Introduction

Decision makers in health care face the challenge of identifying high-value interventions and initiatives which offer a significant return on investment (improved outcomes and reduced burden on health services) in a climate of significant financial pressures. Before investing money, time and energy, it can be argued that a review of evidence and insights is needed, to understand what works, in what contexts and why, and how innovations and improvements can be adapted and implemented locally. This can help avoid the risk of investing in initiatives which offer only marginal benefits or possible harm. However, there are numerous challenges facing managers such as availability and applicability of evidence, timeliness of studies and the ability to translate evidence into action.

In the English National Health Service (NHS), the “Five Year Forward View” strategy (NHS England, 2014) sets out significant change through new care models, which involve transformation of services in hospital, community and general practice settings. To test the new models, NHS England is supporting 50 “vanguard” sites. The vanguard sites are experimental, making decisions and acting in the face of uncertainty – uncertainty which may be narrowed and contained by the careful use of evidence.

Our service was set up to support evidence-informed decision making and are supporting the design, implementation and evaluation of several vanguard sites. Historically, our support has focused on connecting decision makers with research and practice based evidence, through evidence summaries and syntheses. There is a growing recognition of the complexity, ambiguity, volatility and uncertainty (Ghate et al., 2013, The Evidence Centre, 2010) inherent in public service transformation and observers have advocated a “paradigm shift” (Cady and Fleshman, 2012), suggesting planning and evaluating transformative change through a complex adaptive system lens (Snowden and Boone, 2007, Best et al., 2012). Consequently, we felt that a more dynamic approach was needed to capture emerging evidence throughout the lifetime of the programme and to embed evidence within formative evaluation.

Objectives

Decision makers in transformation programmes report significant time pressures. They are often generalists, responsible for a number of different service areas. They need tailored evidence products, offering high level, ready to use guides and tools.

We aimed to respond to this by:

-

– Designing a methodology to help decision makers learn from research and practice and to embed this learning into the formative evaluation of new care models to inform design, implementation and evaluation.

– Developing a pragmatic methodology inspired by the concept of the “living systematic review” (Elliott et al, 2014).

– Creating and testing knowledge products designed to meet the needs of busy decision makers and key influencers.

Methods

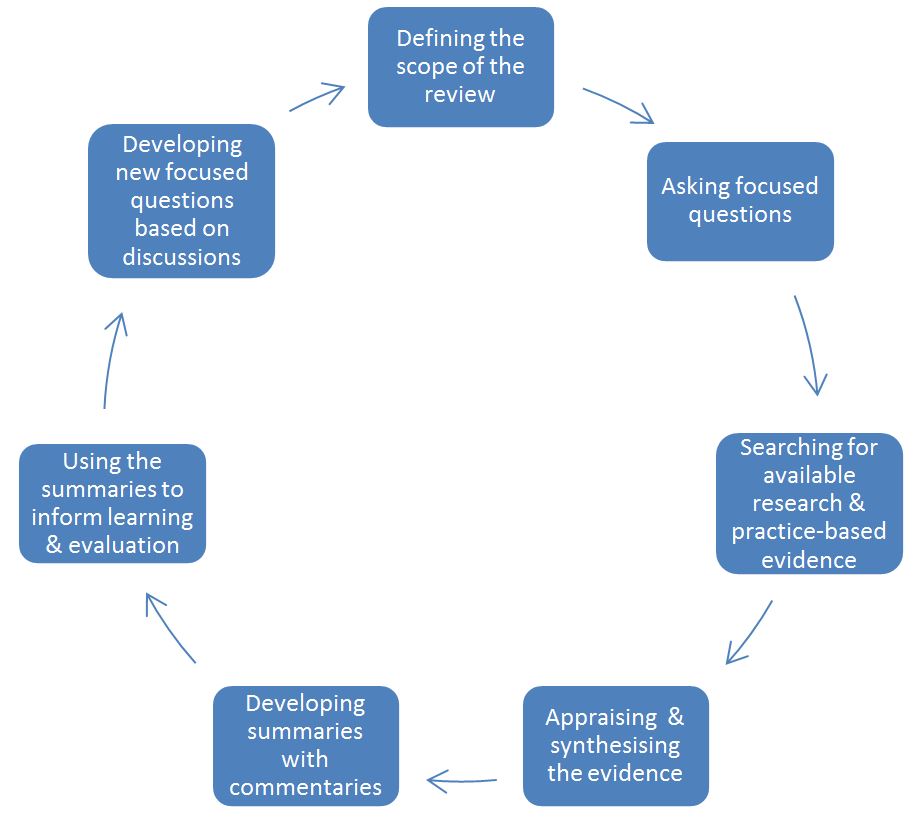

Our methodology involves the following steps:

This places a significant requirement on the ‘demand side’ for the service. In order for the Living Review to add greatest value, it must be asked the right questions by the programme. Over time, more people within the vanguard will become aware of the service and different mechanisms will evolve to shape and guide the work. This function is primarily performed by a Steering Group. For each output therefore, as well as providing a check on the quality of the work, the Group is asked to consider: what are the implications of this evidence for our programme? And, given our context, what else do we need to know?

Results

For the first review, we focused on a broad topic that is a fundamental feature of the Multispecialty Community Provider (MCP) model: primary care at scale. High quality, sustainable primary care services are a tenet of the MCP model; there are broad trends and drivers leading towards larger practices offering a greater range of services (alongside hypothesised benefits to doing so), yet there is no settled consensus on the most appropriate models – or the best ways of bringing them to being. The review also informed local discussion on the shape of primary care services. The review addressed the following questions:

- What are the major challenges currently facing primary care?

- What does primary care at scale look like (from the perspectives of patients, communities, practices, providers, commissioners, partners)?

- What organisational forms might primary care at scale take and what examples are there of existing and planned developments?

- What are the benefits and risks of primary care at scale?

- What are the enablers and challenges in developing primary care at scale?

- What can we learn from experience within the UK?

- What can be learned from the experience of other health systems and from similar strategies in other sectors?

- How might primary care at scale be taken forward effectively?

- What is the role of commissioners and practices?

For the second review we focused on multidisciplinary teams (MDT) in primary care and community settings. A number of themes emerged; including the importance of strategic leadership; the influence of culture on MDT working; challenges in sharing information across sectors and the variation of measures of outcomes. Specifically the review focused on the following questions:

- How are integrated and multidisciplinary teams defined in different contexts? Which services are typically included?

- What are the key components of integrated and multidisciplinary teams? For example, how are patients assessed and targeted?

- How do such teams work in practice? What are the benefits/challenges of working in this way?

- What seems to be most important about the design and implementation of such teams? What seems to work in which contexts and why?

- What effect do teams have on: health outcomes; patient experience; staff satisfaction; workload; emergency admissions; social isolation; sustainability? How are these effects typically measured?

- What lessons does practice elsewhere offer?

The third review is currently in progress and is focusing on what can be learned to inform the formation of accountable care organisations.

Future updates of each living review are influenced by an evidence map approach (Miake-Lye et al. 2015).

Discussion

Embedding the ‘living review’ methodology in the development of new models of care has potential benefits. Enabling stakeholders to develop clear questions in relation to evidence in the development of new models of care has informed local discussion informing future directions and focus.

Feedback from steering groups has been positive and an evaluation process is being developed. The steering group approach has created challenges in addressing different audiences for the review (clinical and managerial) who have expressed different priorities in terms of deciding topics.

The process of updating reviews needs to be considered from the beginning, with the structure and design of reviews needing discussion and a team based approach.

Conclusions

It is clear that there is a role for library and knowledge professionals in supporting the translation of research and experiential learning into actionable and contextualised insights and in encouraging the uptake of evidence by embedding its use in existing programme activities.

There are implications for library and knowledge professionals in terms of confidence and capability; engaging with steering group members, an understanding of evidence and literature synthesis skills are essential.

References

Best, A., et al. (2012). Large-system transformation in health care : a realist review. Milbank Quarterly, 90, 421-456.

Cady SH and Fleshman KJ (2012) Amazing change: stories from around the world. OD Practitioner 44 (1), 4-10.

Elliott JH et al. (2014) Living Systematic Reviews: An Emerging Opportunity to Narrow the Evidence-Practice Gap. PLoS Med 11(2): e1001603. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001603

Ghate, D., et al. 2013. Systems leadership: exceptional leadership for exceptional times: synthesis paper. The Virtual Staff College.

Grint, K. 2008. Wicked Problems and Clumsy Solutions: the Role of Leadership. Clinical Leader. British Association of Medical Managers.

Miake-Lye et al. (2015). What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Systematic Reviews 5:28.

NHS England. 2014. Five Year Forward View. http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf.

Snowden, D., J. and Boone, M., E. (2007). A leaders framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 69-76.

The Evidence Centre. 2010. Complex adaptive systems: research scan. Health Foundation.

Keywords

Innovation, organizational; Evidence-based practice; Information specialists; Information dissemination; Review literature as topic